At the start of the Renaissance the abbot and occultist Johannes Trithemius wrote a book entitled In Praise of Scribes. In it, he attacked the recent invention of printing and celebrates the superior qualities of the pen. How did he get the word out? In print of course. Even Trithemius could see the writing uh, printing, on the wall.

Trithemius also wrote another book, this one about the use of spirits to communicate over long distances. He would have been amazed by the magic of the Internet. Like Gutenberg preceding it, the Internet threatens the previous technology just as startlingly as the press did the scribe, and just like the press it came seemingly out of the air to change everything that came before.

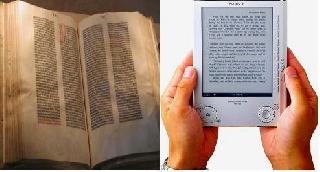

This very abruptness has caught so many off guard it is no wonder the eBook is under a hail of derision. To the unconverted let me remind you, the book is an ongoing project, a largely technology driven enterprise. If the medium in which it has evolved has remained relatively static for the past five centuries, it is not for lack of trying. Gutenberg had applied the available equipment of his age so well there would be no real advancements in printing until the Industrial Revolution and the power of the steam engine.

Unlike Antony, I come not to bury the eBook, but to praise it, and I say this with all the passion of a true book lover. Confirmed bibliophiles will raise their hand's in unison when asked what part of the book stands out the most---the smell. The olfactory experience of a library is like that of incense in a sacred space. Beyond its tactile properties the scent of a favorite title can instantly launch one into the time and place it was first read. Of lazy summer days by the pool, or quiet winter evenings in an armchair.

This, for lack of a better word, "presence" of a book is the first thing the true bibliophile loses when the beloved is consigned to the digital world. Yet, this heavenly scent, so tied to our conception of the traditional book, is relatively recent. Before the Civil War, books were printed with the higher quality, thus more costly rag paper, as it had been for centuries. It is due to its higher quality and durability that the government still uses it to print money. Few of us have been privileged to take in the atmosphere of the Bodleian in Oxford, or to taste with Poggio the treasures of St. Gall. And no man lives that has stood among the numberless scrolls of fabled Alexandria.

We can only guess what delicious bouquet a million volumes of papyrus, coated with cedar oil, may have consisted of. And so the familiar friend in the guise of bound paper and ink is not as eternal and unchanging as we might wish to think. However, we must not forget the first task of a book, to convey knowledge, and to do so as conveniently as possible. For those who have been paying attention, it is obvious how convenient obtaining information is online compared with a trudge to the local library.

The supremacy of the computer is testified to by the role those public libraries are taking in computer training and literacy. What library still uses that arcane relic, the card catalogue? Many booklovers are fearful of hypertext, the idea of imbedding links in the text to related information and perhaps even changing the text its self. For a world so long accustomed to the seeming permanence of print, we have forgotten the age before it when all books were hand written. It was common to include glosses on words that were unusual and annotations or alternative readings in the margins that, sometimes, in later copying were incorporated into the body of the text as though it had been there all along. This occurred in stunning and unexpected ways.

Those familiar with biblical scholarship are well aware of the variant readings of the New Testament that would shock many of those who believe the Bible was delivered from Heaven as an uncorrupted vessel of God's word. Even print has not been totally immune from these practices. The footnote and endnote are less personal yet similar attempts to squeeze the most out of a text for the benefit of the reader. Hypertext is the next logical step beyond the limitations of the page. However, as with most new tools, the world is often slow to adapt.

Meet the eBook, save as the Ol

The eBook is awkward, ugly and plain. Four centuries ago the same was said of print. Duke Federico da Montefeltro, who had assembled one of the finest manuscript libraries of the Renaissance, was heard to remark he would have been ashamed to own a printed book. In the end, we got used to the aesthetics in exchange for convenience. Unlike the Duke, I am fond of that old adage "don't judge a book by its cover".

|

|